In investing much like in football, it pays to make sure you have a strong defensive strategy. In football, that means not letting the opposing team score as many points as your team. I investing that means to keep more of your gains by not giving up as much. Doing this is not trying to time the market but instead taking a disciplined approach in your portfolio, keeping the same allocation but making adjustments based on economic trends. The asset allocation of a portfolio accounts for about 90% of long term portfolio performance, meaning that staying invested and sticking with your asset allocation accounts for the bulk of your expected return. By remaining disciplined and sticking to your asset allocation, you can make the most out of market gains and possibly not get hurt as much by market drops.

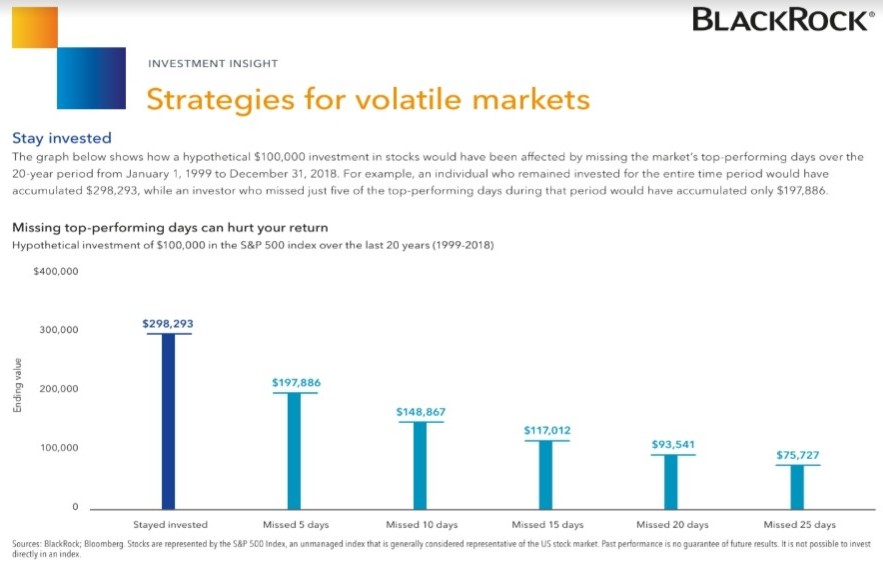

First, lets us look at why trying to time the market does not work. The first and most significant issue with trying time the market is when to be invested and when to be in cash. To do this well, you have to be correct twice. You need to know when the best time to pull your money out if the market is and when the best time to renter the market is. Someone might be able to get this correct once or even twice, but there is no way to guess, and yes, it is guessing, when the right time is consistently.

Secondly, by not staying invested, you risk missing essential market days. The stock market does not move in a straight line. There can be three days that make up most of a year’s return. The chart above shows the value of a $100,000 account invested in the S&P 500 index from 1999-2018. If you had stayed invested the entire 20 years, your account would be valued at $298,293. If you missed the five best days in that time period, your account would be valued at $197,886, a $100,407 difference. If you try to time the market, you run the risk of missing even more than those five days.

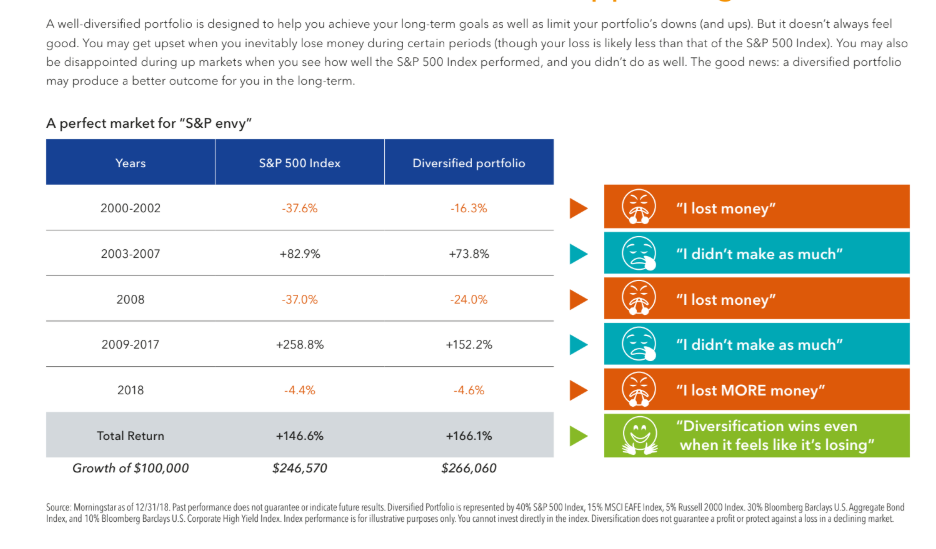

The chart above only looks at the S&P 500 index, which would only be a part of one’s portfolio. By sticking to your asset allocation and creating a diversified portfolio, you can limit the downs and ups of your account balance. The chart below compares the performance of the S&P 500 index to a portfolio that has an asset allocation of 60% stock and 40% bond.

The diversified portfolio performs better over the 18 years, due to it not dropping in value as much. If you can limit the downs in your portfolio, then your ups do not have to be as high.

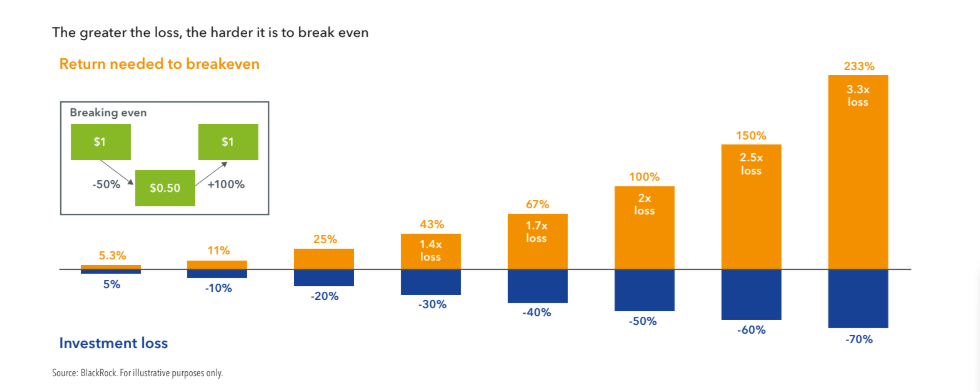

When your account drops in value, it has to return even more to get back to where you started. Using the chart, if your account is worth $100 and drops by -50%, then your account is only valued at $50. To get back to where you started, you will need to earn 100%. If you can limit that loss, then your account will not have to work as hard to get back to even and to grow. So, if you can limit your account to only dropping by 30% rather than 50%, you will only have to recover by 43% rather than 100%.

Now let us put that into a real-world example.

Meet the Smiths, a retired couple who (for purposes of this illustration) have their entire $1 million of savings in stocks. The Smiths hang onto their stocks through a 50% bear market, which lasts 2½ years, as well as a 3½-year bull market that follows (both fairly typical time periods). During the bull market, stocks go up 100%, which we know from Table 1 is exactly the amount necessary to recoup the 50% bear-market loss…at least for investors who leave all of their money in the market.

What makes the Smiths different is that, during the bear market decline and the bull market recovery, they not only have no net return, but they are drawing out money to live on each year. Let’s assume that the Smiths draw out $40,000 every year. That is 4% of their portfolio’s starting value (4% is generally the maximum that most retirees should draw if they wish to maintain their principal).

Unlike in Table 1, after a 50% bear market loss, the Smiths’ portfolio will not get back to $1 million of principal with a 100% bull market gain. They need the bull market to go up considerably more than 100%. Here’s why:

- When the bear market reaches its bottom (down 50%), their $1 million portfolio is actually down 60% ($600,000), so it is only worth $400,000. The reason?

- It dropped 50% ($500,000) due to the bear market, plus

- They withdrew $40,000 per year for 2½ years ($100,000) to live on.

- Referring to Table 1, we can see that a 60% decline (while it doesn’t seem much worse than 50%) requires a lot bigger gain to recoup the loss—150% instead of 100%.

- But the Smiths also draw out $40,000 each year during the 3½-year bull market recovery, so that’s another $140,000 that they need to recoup.

- Note that the $40,000 a year that they are drawing during the bull market isn’t 4% anymore (as it was relative to their starting $1 million).

- Instead, as a percent of the portfolio’s $400,000 value at the bottom, $40,000 is a whopping 10%!

- Summing it up, when they have $400,000 at the bottom of the bear market, they will need to gain $740,000 to get back to $1 million:

- $600,000, which is 150% of $400,000 (as explained in B above), plus

- $140,000, which is 35% of $400,000 (as explained in C above), which all adds up to

- $740,000 total, or 185% of $400,000.

Because the Smiths drew $40,000 out each year to live on, instead of needing the market to double (gain 100%) to get back where they started, they need the market to almost triple (go up 185%!).

(Example from: Why Losses Hurt More than Gains Feel Good: Part 2. Implications for Different Investors)

In the case above, a drop in the Smiths account of -50% is unrecoverable. It is for this reason that you need to have an investment plan in place that matches your asset allocation to your goals. By taking a disciplined approach and using asset allocation, one can diversify out of some of that risk. Now there will always be risks in a portfolio. Still, the amount of risk is relevant to how aggressive or conservative the account is, the more risk in a portfolio, the higher the potential return but also, the greater the potential for loss.

The main point is that by having a diversified asset allocation that matches your goals, you can limit some of your losses and gains, to create a smoother, more beneficial path to retirement. The offensive side of a portfolio might win every few years, but a strategic disciplined diversified asset allocation model will be what takes you through your retirement goals.

Why Losses Hurt More than Gains Feel Good: Part 2. Implications for Different Investors

A Modern Approach to Asset Allocation